Earlier this week, President Trump credited Dallas County, Texas, one of the country’s 10 most populous, for adopting all paper ballots for its elections.

The thing is: The county already uses paper ballots.

As do 99.9 percent of registered voters in the state, and 96 percent of registered voters in the whole country. Those numbers are from Verified Voting, an election data hub with a 50-state, county-by-county map of information about voting methods and equipment.

According to the Dallas Morning News, the mistaken credit is properly owed to a pending decision from the county Republican party, about how it will count paper ballots in its primary elections next March. But that fact is beside a much larger and more consequential point for the whole populace’s understanding of elections: There’s an apparent lack of clarity about the role of paper in them.

The president has called for the widespread use of paper ballots many times before (one such example here), and it’s echoed, regularly, far and wide. Each time it is, it can invite a natural and entirely fair question: Wait, who isn’t using paper ballots? And the answer is, not that many.

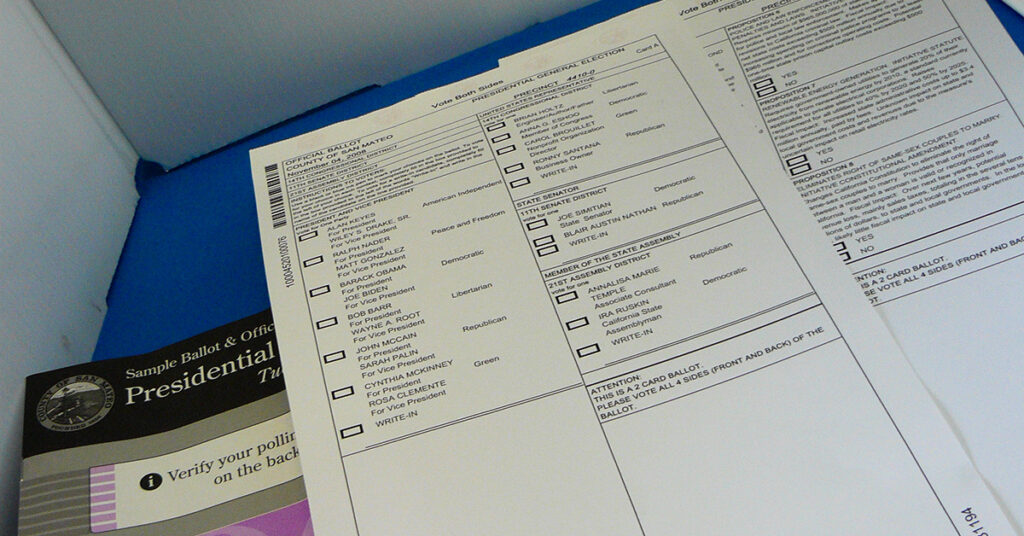

Let’s go back to Verified Voting. According to the comprehensive data it’s compiled, roughly 70 percent of registered voters have lived in election jurisdictions using hand-marked paper ballots since 2016. At that time, the top alternative voting method was called a “direct recorded electronic” voting system, or DRE: “a vote-capture device that allows for the electronic presentation of a ballot, electronic selection of valid contest options, and the electronic storage of voter selections as individual records,” per Verified Voting’s description. This was the process available to about 29 percent of registered voters a decade ago.

Some DREs have the option to print off a paper record of a voter’s choices before submitting the ballot electronically. Others don’t; think of ordering food on a touchscreen and not getting a printed receipt. In 2016, most DREs lacked this feature: in most counties across Delaware, Georgia, Indiana, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Texas (and a handful elsewhere). Together, these places accounted for 22 percent of registered voters nationwide.

This figure has decreased substantially in the time since. In 2020, just 9 percent of registered voters were provided DREs that lacked a paper trail, entirely in Indiana, Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Texas. By 2024, only 1.3 percent were: All of Louisiana, and a few counties in Texas.

The technology that has superseded DREs is called a ballot marking device, or BMD. BMDs don’t submit votes electronically, which is the key difference from a DRE. Instead, voters make their choices on an electronic screen, such as a touchscreen; then print them, able to be inspected; and then submit them, just like they would if they had marked the ballots by hand. Come 2026, BMDs will be used in all of Georgia, Nevada, and South Carolina, and most of Arkansas, Texas, and West Virginia, as well as a smattering of counties in several other states.

All told, here’s one way to think about the recent evolution of paper’s use in the election process nationally: In general, most voters have had at least the option of an auditable paper trail of their choices; now, almost every American voter submits their choices on paper. Whether those choices are made with an ink pen or the ink from a printer cartridge, they exist on something we hold and turn in with our own hands.

That’s how they do it in Dallas; how they do it in America’s most populous (Los Angeles) and least populous (Loving, Texas) counties; how they do it in Key West, and in Alaska, and in almost every place in-between — not to pick on the good people of Louisiana.