Garrett Glover has been the straw that stirs the drink for a while now. As a high-school student, he realized that one of the “Five Cs of Arizona” that represent the state’s economy, citrus, was missing from state insignia. His solution? Petition the legislature to make lemonade the official beverage of Arizona. “A little boy in a classroom, trying to learn about civics, brought it [to the capitol],” said then-Arizona house speaker Rusty Bowers at the time.

More than six years after former Gov. Doug Ducey signed HB 2692 into law, bringing that “little boy’s” work to fruition, Glover still interacts with the state legislature, now in a more formal capacity. His role, however, is uncommon. He is an assistant inside the Pinal County Elections Department, as its de facto liaison to the house and senate in Phoenix. “I was blessed. We hired him just knowing that’s where his heart is,” Dana Lewis, the county recorder since 2022, told Declare.

Glover’s job is a sign of the times. Lewis said that during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, “elections” became a buzz word. Unforeseen numbers of legislators and constituents have wanted their hand in overhauling the process since. Well in excess of 100 pieces of election legislation are now introduced annually in Arizona: a total that most election offices aren’t equipped to analyze, provide feedback on, and prepare for the possibility of implementing. Prior to 2020, that number was routinely between the 40s and 60s.

“I think we were really befuddled about the whole thing,” Lewis admitted. And frustrated.

A flood of paper

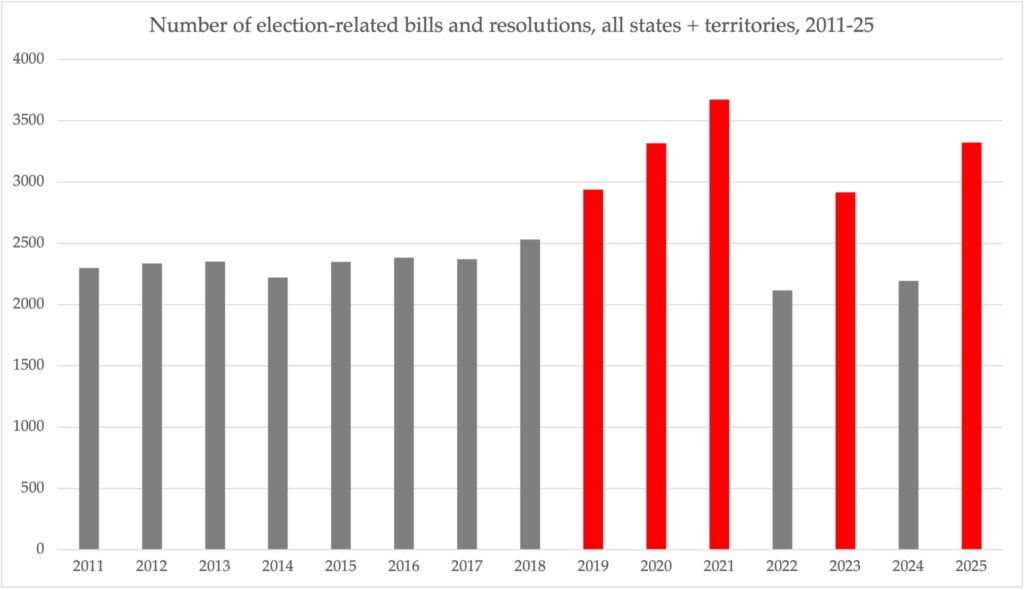

Lewis and Glover’s experience is indicative of a nationwide trend. According to a National Conference of State Legislatures database, there have been five years in the COVID era (2019, 2020, 2021, 2023, and 2025) when more than 2,900 election-related bills and resolutions were introduced in the 50 states and U.S. territories. Between 2011 and 2018, the time for which the NCSL has data, there were more than 2,400 pieces of legislation in a given year only once.

“It can be a lot to keep track of . . . you’ve got to keep tabs on all of them because you never know which one will make it to the finish line,” said Glover.

Lewis added that there are staffing concerns. Pinal County is the third-largest in Arizona and growing; election offices in counties of a smaller size don’t automatically have the luxury of a Garrett Glover around the office. In fact, Lewis said, Glover functions as a resource for other recorders’ offices around the state that have questions about legislation. Then there’s COVID itself. At the time of it and after, Lewis dealt with a lack of employees, saying there was a “mass exodus” of election professionals and poll workers, whether they were sick — or sick of the job. They were missing lunch breaks and a life because of all the changes placed in their laps.

“Then again,” said Lewis, taking stock of the last several years, “they (legislators) are trying to listen to their constituents to fix something that they think was broken, but really wasn’t for the most part.

“Legislators, unless they’ve done these jobs, been a poll worker — if they’ve never administered an election even in a small town, they really don’t know what we’re up against.”

The other side of the process

Pat Proctor sees these issues from the opposite side of the policy-and-administration relationship. A state representative from Kansas and candidate for secretary of state next year, he serves as chairman of the Kansas House Committee on Elections. “It is very complicated, because you have to thread the needle to get at solutions that address security concerns, or voter confidence concerns, without creating an undue burden or making it impossible to vote or costing counties a gazillion dollars,” he told Declare.

Proctor told the NCSL’s media arm earlier in 2025 that his committee had “a banner year,” touting new state laws that require absentee ballots to be received by Election Day and move the period of voting machine testing to an earlier date on the election calendar. Such reforms alter how election administrators have to go about their jobs. Proctor also said he believes they benefit voter trust.

“I try to meet as many of them (county election administrators) so that when we are doing legislation in the legislature, in my committee, we are not unduly burdening them or creating second- or third-order effects that we are not aware of,” he told Declare.

In Pinal County, Lewis’s team already knows that with a small election upcoming in May, she’ll be with legislators this coming January and even before. “We realize if we start the conversations, it’s sometimes received a little more openly,” she said.

“Recognizing that the paradigm has changed and the pendulum has swung, we need to be there. We need to have those conversations and be available for that.”

Part of this includes a greater openness from Lewis’s fellow election administrators to make a presence for themselves in the legislative process. She said that she’s noticed progress. “We finally had some recorders and election directors that I think were more comfortable having those conversations and were more comfortable getting up and speaking at the podium and testifying in front of the legislature.”

If this is the new normal, Glover doesn’t mind. “Recorder Lewis says you get bit by the bug and you just love doing it. I got bit by the bug, young,” he said.

Chris Deaton contributed reporting.