There’s been a flurry of activity on election policy led by Republicans in Congress. On Wednesday, the House was expected to pass a stricter version of the SAVE Act (the “SAVE America Act”) right around the time of publication of this article; Senate majority leader John Thune continues to say that it faces dim prospects on his side of the Capitol. Republican Bryan Steil, chairman of a House committee with jurisdiction over federal election policy, introduced even more ambitious legislation less than two weeks ago, the Make Elections Great Again (MEGA) Act.

With congressional action likely to stall, however, a hearing that Steil’s panel held on Tuesday teed up a more practical way to think about Republican demands — than thumbing through a hundred pages of bill text, anyway. Subtitled “How to Restore Trust and Integrity in Federal Elections,” Steil listed his goals [numbers mine]:

“Here’s the top line: (1) Elections should end on Election Day. (2) You should need a photo identification to cast a ballot. (3) You must be a citizen of the United States of America to vote in a federal election. (4) You need auditable paper ballots. (5) And we shouldn’t be sending ballots to people that don’t request them,” he said. “These reforms alone will improve voter confidence, strengthen election integrity, and continue to make it easy to vote and hard to cheat.”

If that’s the case, then to what extent do existing state and federal laws do the trick? The SAVE Act, SAVE America Act, and MEGA bill are based on the belief that Washington should take a much larger role in what Republicans would call election integrity — just like the Democratic-led For the People Act was premised on supporting a much bigger federal role for expanding vote methods and accessibility. The Constitution does give Congress power to set the “Times, Places and Manner” of federal elections should it choose, but states, by the Constitution and tradition, generally get first dibs. It’s all a matter of where to draw the line. Where does it belong, going just from Steil’s own list?

(1) “Elections should end on Election Day.”

Fourteen states plus Washington, D.C., have laws allowing mail ballots that are postmarked by Election Day to be counted, even if they arrive a certain number of days “late” (it varies by state). Clarifying language about the timeliness of postmarks and new mail processing standards from the Postal Service could delay the status of these kinds of ballots; Declare’s Miranda Combs is covering the story extensively.

Additionally, 29 states plus D.C. permit late-arriving ballots from military and overseas voters: 19 require a postmark on or before Election Day, and 10 do not, having a mix of other standards.

It’s vital to note the partisan breakdown of these states. They’re red, they’re blue, and they’re purple: Texas, California, and Virginia permit post-Election Day mail ballots for all voters, for example. It wouldn’t be credible to call this a blue-state issue; instead, it’s closer to an issue of state legislatures exercising their own preferences.

A Supreme Court case to be argued in March will settle this matter for at least the 2026 elections. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in October 2024 that federal statute defining the first Tuesday in November as “Election Day” invalidated state laws allowing late-arriving ballots: “[F]ederal law does not permit the State of Mississippi,” the party to the case, “to extend the period for voting by one day, five days, or 100 days,” the majority’s opinion reads. Mississippi’s appeal is that the act of voting is distinct from any step in the election process that follows, and late-arriving ballots are therefore legal if they’re cast by Election Day.

But note especially this additional language from the state’s initial petition, filed in June 2025: “The [Fifth Circuit’s] decision below . . . invites nationwide litigation against laws in most States—risking chaos in the next federal elections, particularly given the tendency of election-law claims to spur last-minute lawsuits. Less than 18 months remain before the next federal election—and state electoral processes start much sooner.” That was eight months ago. Primary elections in some states now start next month.

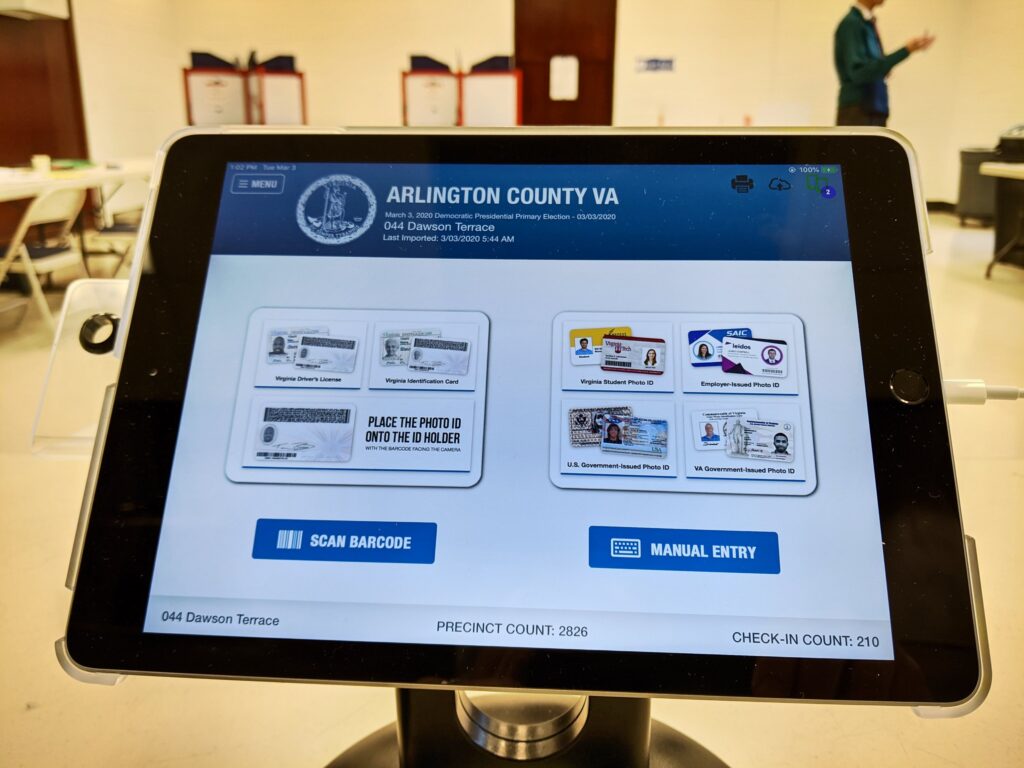

(2) “You should need a photo identification to cast a ballot.”

Voter identification — of which photo identification is a subset — is a complex issue state-by-state. First, “voter ID” refers to identification presented at a polling place. Prior to then, an applicant for voting in federal elections is required by the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA) to, in general, provide a state-issued ID number (e.g., driver’s license), the last four digits of their social security number, or else take state-specific steps to confirm identity. On that same form, a registrant must sign, under penalty of perjury, that they meet the standards for voting in federal elections, including citizenship and minimum age. States confirm identity and eligibility from there with the relevant government databases.

Second, in total, there are 36 states that require or request voter ID of some sort, and 14 plus Washington, D.C., don’t. The National Conference of State Legislatures sort the 36 states into four categories: a strict photo ID (10 states) or non-photo ID (3) requirement, which mandates that voters without their documentation cast a provisional ballot and take further steps post-Election Day; and a photo ID (14) or non-photo ID (9) request, which provides alternatives with lower thresholds to voters who don’t furnish the necessary ID. The NCSL maintains a list of how the other 14 states and D.C. without voter ID provisions in state law conduct voter check-in and follow-up at polling places.

Whether this particular lack of uniformity is a problem is debatable; that it exists is not.

(3) “You must be a citizen of the United States of America to vote in a federal election.”

This one, by contrast, is easy. Section 217 of The Immigration Control and Financial Responsibility Act of 1996 makes it expressly unlawful “for any alien to vote” in a federal election, under penalty of fine, imprisonment, ineligibility for citizenship, and/or deportation. Several states have begun to adopt clarifying language in their own state constitutions, and some have begun to take and share the findings of noncitizen-specific audits of their rolls. None have uncovered numbers that even begin to approach “significant,” in that they could affect the outcomes of races, much less when accounting for the unlikelihood that such votes break all one way or the other. This is different from saying that states shouldn’t check for noncitizen registrations and votes — of course they should. “Whenever an election administrator has performed an audit, very few noncitizens are registered. Even fewer, if any, vote,” former Kentucky secretary of state Trey Grayson told Declare in our report on the issue in November. “We should always be vigilant to keep it that way. After all, we want Americans to trust our elections.”

(4) “You need auditable paper ballots.”

This one’s straightforward, too. According to the election systems tracker Verified Voting, almost 99 percent of registered voters live in jurisdictions that will vote this year on one of: hand-marked paper ballots (69 percent), electronically marked and printed ballots (27 percent), or a device that submits ballots electronically but prints a paper record (3 percent). Louisiana is the outlier, which uses outdated electronic submission machines with no paper records.

(5) “And we shouldn’t be sending ballots to people that don’t request them.”

Eight states (seven in the West), and Washington, D.C., conduct mostly or all mail elections, in which all registered voters are mailed a ballot. North Dakota counties and sparsely populated Nebraska counties are permitted by state law to opt into all mail elections. Several more states allow small, non-federal elections to be conducted all by mail.

Utah is the one truly red state in the first category. According to a poll last year sponsored by the Utah-based Deseret News and University of Utah, only 11 percent of registered voters there oppose mail voting. Fifty percent support automatic receipt of ballots, and 30 percent support a new system in which voters have to opt in once every eight years to receive them.

***

In order of most to least uniform state-by-state, Steil’s list proceeds like this: From (3) and (4), in which the problem is already addressed by existing law or practice; to (5), because it’s only most Western states (and Vermont and D.C. in the East) that use mostly or all mail elections; to (1), because 14 states have late-arriving mail ballot statutes, but twice as many have such policies for military and overseas voters; to, lastly, (2), a patchwork of voter ID requirements.

Together, does this merit such comprehensive legislation as the MEGA bill, or more targeted, yet still disruptive legislation such as the SAVE or SAVE America Act? A strong answer would account for federalism, and for the difference in magnitude between the evidence of the problems being addressed and the specifics of the proposed solutions — just as it was when federal Democrats controlled the House and proposed their mirror of widespread election reform a half-decade ago.